About wood block printmaking, also called xylography.

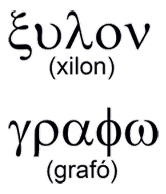

Etymologically, the word xylograph is composed by “xilon”, from the Greek, and by “grafo”, also from the Greek. “Xilon” means wood and “grafo” means to engrave or to write. Therefore, a xylograph is a print made from a wood engraved block. In a simpler manner, one can say that it is a printing process which uses a wooden stamp.

It is not known exactly when woodcut printing began to be used or who invented it. Among the knowns, the oldest paper woodcut print illustrates an issue of the Buddhist prayer Diamond Sutra, published by Wang Chieh, in China, in 868. It is, however, believed that centuries before, the Far East woodcut printing artists were already stamping fabrics, perhaps initially in India. In Europe, the most remote testimony is a piece of fabric stamped in the twelfth century. There are, however, some people who claim that European fabric stamping exists since the sixth century. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the Europeans widely used woodcut printing to produce sacred images (saint images) and decks of cards.

Afterwards, some artists raised woodcut printing to higher levels, especially Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), from Germany, who inaugurated a new chapter in this form of art, with the Apocalypse series (1499), in which he developed tracings in search of the potentialities of wood, attaining a peculiar and remarkable plastic language. Dürer’s print’s greatly influenced illustration in Germany.

Italy was another woodcut printing excellence center in the Renaissance period, especially the cities of Venice and Florence. Although subordinated to book illustration, woodcut in Italy developed its creativity, thanks to the miniaturist tradition in which Italians exercised a certain ornamental freedom.

However, when it was already spread throughout Europe, woodcut printing happened to lose space. From the sixteenth century on, etching and metal engraving appeared as a very strong competitor. At that time, wood engraving printmaking was not yet used, and etching and metal engraving would allow attaining images richer in delicate traces and in fine minutia, impossible to be made in woodcut printmaking. This proved to be an advantage that overcame its disadvantage of needing a second printing due to the fact that the metal is inked in a manner different than that employed in typography, which is a relief block technique.

Meantime, on the other side of the world, in Japan, wood engraved printings experienced a magnificent splendor moment with the Ukyio-e School. Produced mainly in Edo, currently Tokio, from the seventeenth century to the nineteenth century, Ukyio-e printings represent woodcut’s first liberty movement from books. Printed in detached paper sheets, in huge numbers, countenanced by the work of teams of engravers and printers gathered in collective workshops, it met, with its abundant colors as well as landscape and daily life descriptions, the taste of salesmen. The highest exponents of the Ukyio-e wood printing were Utamaro Kitagawa (1753-1806), Hokusai Katsushira (1760-1849) and Hiroshige Ando (1797-1858).

At that time in Europe, wood printing was once again being widely used to illustrate books, newspapers and magazines, thanks to the new techniques of wood engraving, which, during the nineteenth century were diffused by the hands of the English engraver Thomas Bewick (1753-1828). In 1775, Bewick won the engraving prize of the London Art Society and initiated the ruling of the wood engraving printmaking, which lasted for one century with no rivals and sustained many collective workshops to meet the large demand from publishers. However, such illustrative wood engraving printmaking – usually called reproduction prints or interpretation prints – collapsed in the twentieth century, because of the advantages of the innovative metallic cliché, then widely spread, which derived from photography combined to chemical corrosion of metals.

By losing its useful function – which condemned reproduction engravers to unemployment – wood printing however experienced a magnificent resurrection, although specifically in the artistic field. Liberated from being subservient to orders from communication means, it began to be used with creative freedom by plastic artists enthused with the power of such a plastic language, in which dramatic black and white contrasts are evident. Some of the predecessors of this new phase in Europe were Felix Valloton (1865-1925) from Switzerland, Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) from France and Edvard Munch (1863-1944) from Norway. Afterwards, the German expressionists (Kirchner, Heckel, Schmidt-Rottluff, Nolde etc.) of the Die Brücke group (1906), and at the same time the French fauvists (Matisse, Derain, Dufy and Vlaminck), elevated woodcut printing to an extraordinary expression level.

In Brazil, the same evolution was witnessed: while reproduction prints lost space, liberated artistic woodcut printing came to light, having as its initial pillars Osvaldo Goeldi (1895-1961) and Lasar Segall (1891-1957), and, in the next decades, it became richer with a large number of relevant artists. At the edges of such erudite art, a whole league of creative engravers bloomed in Brazil, originated from typography printing shops linked to the “cordel” literature(*), which roots stretch back to the northeastern singers.

(*) “Cordel” literature is the Brazilian denomination of unpretentious publications sold at folk fairs, mainly in Brazil’s northeastern region. Its texts (in rhymed poetry) were typographically printed and frequently illustrated with woodcut prints. Its name derives from the pamphlets being usually hung from a string, a “cordel”, to be displayed for sale.

Av. Eduardo Moreira da Cruz, 295,

Av. Eduardo Moreira da Cruz, 295,

Campos do Jordão - São Paulo - Brasil